En optant, après avoir longtemps hésité, pour l’installation de leur futur Etat juif en Palestine, et pas ailleurs (Ouganda, Argentine …), les partisans de Theodore Herzl avaient rapidement pris conscience qu’il visaient une région plutôt aride de la planète, où la ressource en eau a toujours été limitée.

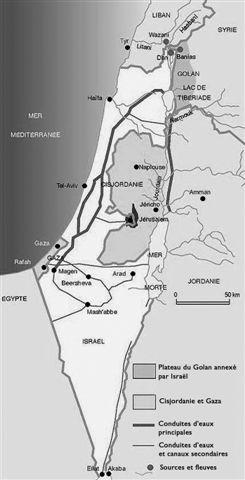

C’est bien pourquoi, au lendemain de la Première Guerre Mondiale, les responsables de l’organisation sioniste ont formulé, à l’attention des deux nouvelles puissances tutélaires du Proche-Orient (Grande-Bretagne et France), des demandes territoriales incluant la plus grande partie des eaux de la région : ensemble du système du Jourdain, jusqu’aux sources du fleuve sur le Mont Hermon, et contrôle du Litani, fleuve du Liban. « Le mont Hermon est le véritable père des eaux de la Palestine ; il ne peut en être séparé sans que cela porte un coup fatal aux racines mêmes de sa vie économique », écrivait déjà le chef de l’Organisation sioniste Chaïm Weizmann, en février 1919.

La guerre de conquête de 1948 ne permet pourtant pas à l’Etat juif de s’emparer du Litani, ni de la totalité du système du Jourdain, dont une partie seulement se retrouve sur son propre territoire.

Mais si cette première guerre n’apporte pas l’eau convoitée, c’est l’eau qui apportera la guerre.

En 1963, Israël achève les travaux d’un grand canal de dérivation du Jourdain en direction du désert de Tel-Aviv et du Neguev, qui a pour effet de réduire le débit du fleuve et d’en augmenter la salinité. Les Etats voisins, Syrie et Jordanie, répliquent en tentant de détourner les eaux d’un affluent du Jourdain, le Yarmouk, mais l’aviation israélienne bombarde systématiquement les chantiers, et ils renoncent.

En 1967, la guerre dite des « Six Jours », succès militaire complet pour Israël, lui donne finalement le contrôle total des eaux de la région, à l’exception de celles du Litani.

Les Palestiniens de Cisjordanie et de la bande de Gaza sont les premières victimes de la politique israélienne dans le domaine hydraulique. L’occupant leur interdit de creuser des puits sous leur propre sol, leur impose d’acheter à des prix exorbitants (plusieurs euros le m3 !) l’eau de la compagnie israélienne Mekorot, laquelle n’a pas investi un centime en 40 ans : 40% des villages de Cisjordanie sont toujours privés de réseau, et les installations des villes, préexistant à l’invasion israélienne, sont en ruine. Inversement, les colons font un usage immodéré des maigres ressources, à tarifs subventionnés, tant pour l’irrigation agricole que pour leurs loisirs, avec piscines et terrains de golf.

Le droit international s’est doté de textes faisant obligation à chaque Etat, même en situation de conflit, d’utiliser l’eau de manière « raisonnable » et « équitable ». On en est loin.

Par CAPJPO-EuroPalestine

ENGLISH TEXT——————————-

1963

Water: a shared resource?

In opting, after much hesitation, to set up their future Jewish state in Palestine (as opposed to Uganda, Argentina or other potential locations), the partisans of Theodore Herzl quickly became aware that they were looking at one of the more arid regions on the planet, where water, as a natural resource, was scarce.

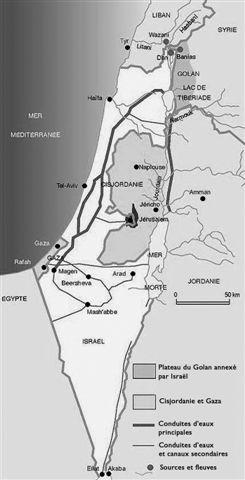

For this reason, in the aftermath of World War I, water was a primary ingredient when the leaders of the Zionist organization formulated their territorial demands to the new title-holders of the Middle East: Great Britain and France. Thus, the Zionists’ asked for the greater part of the region’s watersheds, the entirety of the Jordan River all the way to its source on Mount Hermon as well as control of the Lebanese river, the Litani.

Mount Hermon is the true father of the waters of Palestine, so it cannot be separated from our territory without leading to a fatal blow against the very roots of economic life, wrote the head of the Zionist organization, Chaim Weizmann, in February 1919.

However, the war of conquest in 1948 did not enable the Jewish state to take over the Litani river, nor did it capture the whole of the Jordan basin, only a part of which ended up in Israeli territory.

But if this war did not bring the coveted water, it was water that brought more war. In 1963, Israel completed a large canal in order to divert the Jordan River in the direction of Tel Aviv and the Negev desert, which resulted in reducing the overall flow and augmenting the river’s salinity.

The neighboring states, Syria and Jordan, replied by trying to divert the waters of a tributary of the Jordan, the Yarmouk, but the Israeli air force systematically bombarded the work sites and the project had to be abandoned.

In 1967, with the so-called “Six Day war” a total military success for Israel, the victors finally got control of all the region’s waters, with the exception of the Litani.

The Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza Strip were the first victims of Israeli water politics. The occupier prohibited them from digging wells under their own land and then imposed an exorbitant price (equivalent to several Euros per cubic meter!). Benefiting from the sale of water was the Israeli company Mekorot, which had not invested a single cent in 40 years. Forty percent of West Bank villagers were now excluded from the water distribution network. Water infrastructure in West Bank towns, which pre-dated the Israeli invasion, was left in ruins.

On the other hand, Israeli settlers were given inordinate use of this meager water resource, at subsidized prices for agriculture and even water-devouring leisure structures such as swimming pools and golf courses.

International law is abundantly clear in obligating each and every State, even in situations of conflict, to use water in a reasonable and fair manner. This is far from the reality on the ground.

by CAPJPO-EuroPalestine